What’s In a Game: The Ten Button Theory

What makes a good game – elearning or otherwise? As I’ve been working on a few different learning games recently, it became clear that some people are intimidated by the idea of using gamification because it seems too complex or overwhelming. So I wanted to share some of the ways I’ve learned to break down the complexity, and help bring great gamification to your training.

Left, Right, or Down the Center

When it comes to making a good game, some designers overthink the process. People talk about buttons and scores as being “gamified” and those can be pieces to consider. But in order to know how to make a game you have to break down its components.

The most rudimentary aspect of a game – before the interface, the score, and the rules (at least in virtual games) – is the controls. Do you remember the Nintendo Entertainment System controller? If you don’t, I’m sad for the hole in your life.

There are only four interaction items, or buttons, on the controller. Excluding Start and Select, there are only input options – A, B, Up, Down, Left, Right, Up-Left/Right and Down-Left/Right. In the end, it’s a very simple control scheme. But from that 10-button scheme has come more than 700 video games for NES alone. The simplicity of these controls reveals a fundamental truth about video games: they are all multiple-choice questions.

D) All of the Above

Granted, video games are likely the most complicated and interactive multiple-choice questions we will encounter, but ultimately they are all multiple choice with different looks. The first Super Mario Bros. game was simple A/B options. Left/Right? Jump/Don’t jump? Run/Walk? The rest was up to timing. Even the more sophisticated modern games like Halo are just a complicated series of multiple choice questions.

What then makes these games different from one another? How could Nintendo become so massively successful on such a simple control scheme? Metaphor.

A Rose by Any Other Name

Metaphor forges the world around us. Guy Deutscher said in his book The Unfolding of Language that almost every word in any language is a metaphor. As an example, he explains the original meaning of the word sarcastic. Go back a few hundred years and sarcastic meant to rend the flesh, but at one point someone began using sarcastic to describe another’s speech. Thus the metaphorical ball of metaphor rolls on.

Metaphors in Games

If the entire world is a metaphor, then games, even corporate training games, are no exception. Early video games were metaphors tied to simple controls. As controls evolved and got more complex, producers were able to use more interesting metaphors.

In 2005, RedOctane and Harmonix realized they could create a controller like a guitar and Guitar Hero was born. Nintendo came out with the Wii, which allowed users to influence the game with body motion and flicks of the wrist, leading to more nuanced games like Wii Sports, Metroid Prime: Echoes and The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess.

Focus on Elearning

But how does this apply to elearning? Instead of focusing on controls, we focus on performance and learning objectives. What is being taught, and what metaphor will make the subject matter more understandable and engaging? I know the concept sounds boring, but doing this well means your elearning games won’t be.

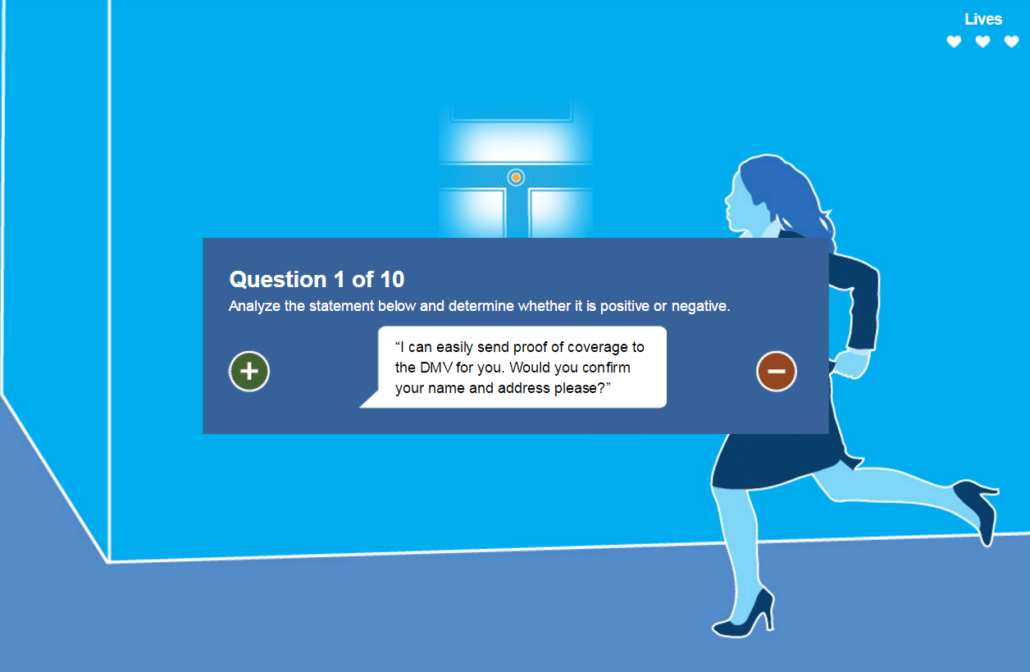

For example, when creating customer service call center training, we had to teach learners to recognize the difference between positive and negative language and how to make a typically negative comment into a positive one. The first draft of the game was a simple true/false choice (A/B in game jargon). Something about this didn’t quite feel right, so I worked with David Horrocks, one of our amazing art leads, on a new concept.

Gamifying the Metaphor

We hit on the idea of a maze. It helped tell the story of positive and negative language more clearly. Mazes represent duality of choice – left/right, front/back. They also represent something confusing, much like the fine difference between positive and negative language.

Then I started to consider the mechanics. We have a learner enter a maze of negativity and they have to make these negatives into a positive. Without revealing everything about how it works, by the time we were finished I was so excited to get this activity out. After we’d applied other game mechanics and the art, I could easily say that it was the best game or learning activity I’d ever created.

Looking at games as a whole, they can seem daunting to design. But when you break them down into the components, it becomes clear. Look at what you’re trying to teach, consider the controls you’re able to use, think of a metaphor for the objective, then apply game mechanics. This forges unique, visually stunning, engaging learning games.